Rojava

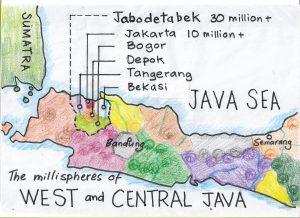

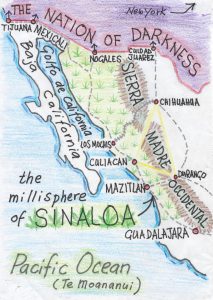

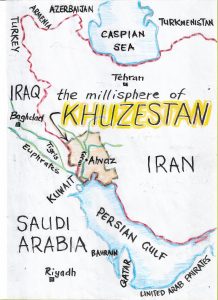

Millisphere: a discrete region inhabited by roughly one thousandth of the world population.

I first noticed Rojava (northeast Syria) a decade ago – while running my millisphere model through a philosophy of the science of geography paper. At the time Syria was in the grip of the 2006-2010 drought (probably caused by climate change). Large areas of Syria’s crop lands were turning into desert and by 2009 their cattle herds had been reduced in number by 80%. Desperate farmers were migrating to the cities.

The Arab spring of 2011 was the spark that started Syria’s civil war but there were pre existing factors. Drought, ethnic factions, economic divides, religious differences and rapid population growth all contributed. Before 2011 Syria’s population had been doubling every twenty years – since 2011 the population has dropped from 21 million to 17 million today.

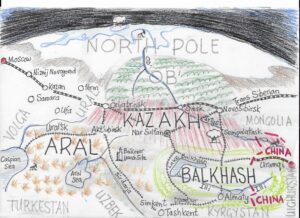

Roughly 40 million Kurds live in the mountainous region where the states of Syria, Turkey, Iraq and Iran meet. In 2005 Abdullah Ocalan, the founder of the PKK (Kurdish Workers Party), proposed a “border-free confederation” of North Kurdistan (S.E. Turkey), West Kurdistan (N.E. Syria aka Rojava), South Kurdistan (N. Iraq) and East Kurdistan (N.W. Iran) – neatly equating to four millispheres.

Originally from Turkey, Abdullah Ocalan lived in Syria from 1979-98 before he was captured by the Turks – with the help of the CIA. Ocalan has been banned from holding public office for life and has been held on the Turkish prison island of Imrali since 1999.

While in prison Ocalan discovered the writings of the American anarchist philosopher Murray Bookchin (The Ecology of Freedom, 1982). Abandoning his Marxist/Leninist beliefs, Ocalan embraced Boochin’s Libertarian Socialism which amongst other things doesn’t believe in capitalism, the nation state or the United Nations.

The Syrian branch of the PKK embraced Ocalan’s ideas and in 2011 the Kurds formed the YPG (People’s Defence Units) and the YPJ (Women’s Protection Units) and entered the Syrian civil war. In 2012 Bashar Assad’s forces withdrew from Rojava leaving the Kurds in control of half of Syria’s oil fields – and the United States put the PKK on its list of foreign terrorist organisations.

The Kurds have administered N.E. Syria since 2014 “working voluntarily at all levels to make Ocalan’s experiment successful.” Based on a bottom-up direct democracy with no hierarchy or party line they set up self-governing sub-regions. Ocalan was critical of nationalism and the Kurds instead proposed a democratic confederation within Syria obeying all Syrian civil laws. So as not to inflame Assad’s government they called their autonomous region NES (North East Syria) instead of Rojava.

In jail Ocalan wrote a book on feminism – his sister had been in a forced marriage – and he was for gender equality. The Kurds in Rojava have banned child marriages and polygamy and a 40% gender quota is required on all councils for a vote to take place. All men entering the Kurdish army take a compulsory class on feminism – highly unusual in the Middle East.

Rojava’s PEP (People’s Economic Plan) proposes “moving beyond capitalism”. Private property and entrepreneurship are protected “by the ownership of use” – but there was to be no absentee ownership. In Rojave there are no direct or indirect taxes and government services are funded through the sale of oil.

From 2014 to 2017 ISIL (the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant) controlled large areas of Iraq and Syria. The Kurds (both in Syria and Iraq) played a major role in the defeat of ISIL. Women YPJ snipers with antique Kalashnikovs were deployed to the front line where they proved to be very accurate. In October 2019 the Kurds led the American Special Forces to a tunnel NW of Idlib where Abu Bakr al-Baghadadi detonated his own suicide vest and that was the end of the first caliph of ISIL.

Turkey meanwhile vehemently opposes Kurdish autonomy in Syria and has moved its forces across the border into Rojava. Trump’s sudden pullout of US forces shortly before the Turkish invasion was seen as a “serious betrayal” of the Kurds who have “no friends but the mountains.”

Nanaia Mahuta should ask president Erdogan of Turkey to free Abdullah Ocalan. Twenty years is a long time for starting a political party.