Kazakhstan – divided into Millispheres

Millisphere: a discrete region inhabited by roughly one thousandth of the world population; around eight million but anywhere between four and sixteen million will do.

Back before Covid, when one could still contemplate traveling, my dream list of potential journeys included the Northern Silk Route through Central Asia.

In the 1980s Olive Newland had gone to Urumqi in the far west of China, traveling as an elderly Whanganui woman by herself. From Urumqi Olive took the southern route across the Tarim depression and over the Karakoram Pass and down the Indus to Pakistan. Olive survived only to die in a car crash in Westmere.

The Northern Silk Route follows where the life-giving waters of glacier fed rivers meet the desert lowlands, passing through the region that gave us the apple, peach, apricot, walnut and almond as well as cannabis and scented roses.

From Urumqi the northern route goes to Almaty in Kazakhstan and a decade ago my friend Blackie the cowboy carpenter arrived in Almaty on a flight from Amsterdam. Slightly drunk, wearing jandals and without a visa, Blackie had planned for his brother Mike, who was teaching in Kazakhstan, to help him get in – but Mike wasn’t there. Kazak customs were suspicious of all the different stamps in Blackie’s passport. “International traveler eh!,” sneered the uniformed customs officer in an oversized, braided Russian cap and Blackie caught a glimpse of his brother arriving as he was frogmarched onto the next flight to Schiphol.

Blackie never made it to Almaty but my friend Chris, the international English literature teacher, had spent a year working there as well as doing another stint in Uralsk, in Kazakhstan’s far west, where the temperature goes from minus fifty celsius in the winter to plus fifty in the summer.

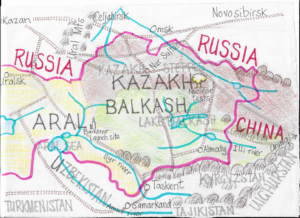

Kazakhstan (2020 population 18 million) by my rules is too large to qualify as a millisphere and we ended up dividing Kazakhstan by watersheds into the millispheres of Aral, Balkhash and Kazak (see map).

Before examining Kazakhstan through my human geography model of the millisphere we should pause to look at Halford MacKinder’s influential 1905 “Heartland” geopolitical model. Mackinder saw the world through the lens of the British Empire. British control of its empire was only possible through being the world’s preeminent navy, he reasoned, and its ultimate threat was from the centre of Eurasia – far from Britain’s navy. Britain’s bogeyman at the time was Russia whom they feared would invade India – overland.

MacKinder’s mythical “Heartland” coincides with present day Kazakhstan. MacKinder’s homily that “whoever controls Eastern Europe controls the Heartland and whoever controls Heartland controls the ”World Island” – being all of Europe and Asia – resonated with the postwar United States, inspiring a Cold War with the Soviet Union. If anyone controls the “Heartland” today it is China but MacKinder didn’t see China coming.

In 1991 the USSR shattered into the independent states we see today. The Baltic “republics” lead the way as the peripheral states broke away and when Russia finally declared independence Kazakhstan was left as the last member of the USSR.

Geopolitics credits geography with determining the rise and fall of empires – twentieth century thinking. The millisphere model credits human geography with revealing the relationship that we humans have with our environment – twenty first century thinking.

Central Asian physical geography starts with plate tectonics. Mountain ranges like the Himalayas, Pamir, Tien Shan and Hindu Kush thrust up as land masses collide and, like an old fashioned hub cap crumpling, depressions like the Tamin and the Caspian plunge to below sea level.

Of the three millispheres of Kazakhstan two (Aral and Balkhash) drain into inland seas and lakes – the Aral Sea and Lake Balkhash respectively. One millisphere (Kazak) drains north into the Ob river in Russia which discharges into the Arctic. A common theme is the environmental degradation of these landlocked seas as rivers were harnessed for irrigation.