Brandenburg

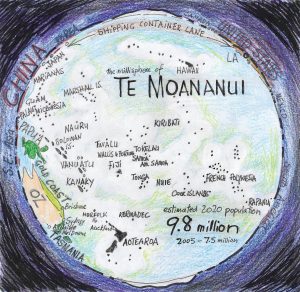

Millisphere: a discrete region inhabited by approximately one thousandth of the world population – around eight million people.

The millisphere of Brandenburg (the Berlin/Brandenburg metropolitan region: six million people) came to my attention when Holly (born and raised in Whanganui) bailed from Berlin and repatriated to Whanganui.

“Why did you leave Berlin?” I had asked her. “After the baby was born everything changed”. Instead of the party scene that drew young people from all over the world lockdown with a newborn wasn’t as much fun; besides, “poor but sexy” Berlin was rapidly gentrifying and even before Covid the young international set were heading for cheaper cities like Leipzig, Warsaw and Lubyanka in Europe and Mexico City and Sao Paulo in the Americas.

In the middle ages Berlin was on the east/west trade route roughly where Europe divided from Frankish to Slavic. In the sixteenth century Berlin went Lutheran and half of the population was killed during the Thirty Years War (1618-48) which started as a conflict between German protestants and catholics.

Berlin became the Prussian capital, German states unified and Berlin became the capital of the “German Empire” and in the twentieth century Prussia was subsumed into Adolf Hitler’s “Third Reich”.

Under the Nazis “the mother of all airports” was built at Tempelhof, outside Berlin. Hitler’s architect Albert Speer’s megalomaniac vision for the “world city of Germania” was made manifest at Tempelhof. Pre WWII Tempelhof was the world’s busiest airport. With huge arc shaped hangers it has been described as the “one of the really great buildings of the modern age”. Tempelhof ceased operating in 2008 and today is used as a recreation zone and recently a refugee camp for Syrians.

During the Cold War West Berlin found itself an island in Soviet Russian controlled territory and when the communists closed all land access West Germany was faced with the choice of abandoning Berlin or supplying it by air. Tempelhof became the destination for the Berlin Airlift and by 1954 was the 3rd busiest in Europe. The fall of the Berlin wall in 1989 spelled the end of Tempelhof which was replaced with a modern airport with longer runways at Brandenburg.

During the cold war West Berlin suffered economically from regional isolation and from 1979-81 self organised squatter communities occupied abandoned apartment blocks. Starting with DIY reconnections of water and electricity, then knocking out walls and reconfiguring architecture, by 1981 there were 168 houses occupied creating a large and vibrant counterculture scene – and conflict with authority. Evictions were met with protests but some 77 squats secured contracts to occupy.

In 1988, a year before the fall of the wall, squatters occupied a piece of bare land which was technically in East Berlin but the wall had been built in the wrong place and in 1989-90 “black living” moved into East Berlin proper. Because people were excluded the east/west border had become a nature corridor.

Since German reunification the capital moved from Bonn back to Berlin. Property speculators piled in to take advantage of the boom and worked with police to evict the squatters “keeping Berlin weird” and gentrified the old apartment blocks. Berlin, like many western cities, now suffers from the lack of affordable housing and in 2017 prices increased faster than any “world city’.

Brandenburg is low lying and flat with chains of lakes and forests that make it very beautiful. The villages and towns in the old East Germany have retained a lot of their heritage values. Berlin itself is a very livable “Green” city of parks and bike paths. Berlin is a “low emission zone” and a green sticker is required to drive a car into the city. Berlin is also the most multicultural German city and is the largest Turkish city outside Turkey.

Post Covid people like Holly are making do with places like Whanganui to congregate. I heard one describe Whanganui as a “a sublimbly pretty town which hasn’t had the heritage knocked out of it, is two-and-a-half hours from Wellington, has an airline to Auckland that gives you Tim Tams, has an art scene and an independent bookshop; it’s a place where you can manage a work life balance with ease.”